The fictional county in Mississippi that author William Faulkner fashioned to serve as the setting for his books and short stories is coming to life in the Digital Yoknapatawpha project, an online mapping initiative led by some two dozen Faulkner scholars from around the country, including Dr. Jennie Joiner, associate professor of English.

“Dr. Joiner’s participation in this important and prestigious digital humanities project promises to raise Keuka College’s profile significantly in the field of digital scholarship,” says Dr. Doug Richards, professor of English.

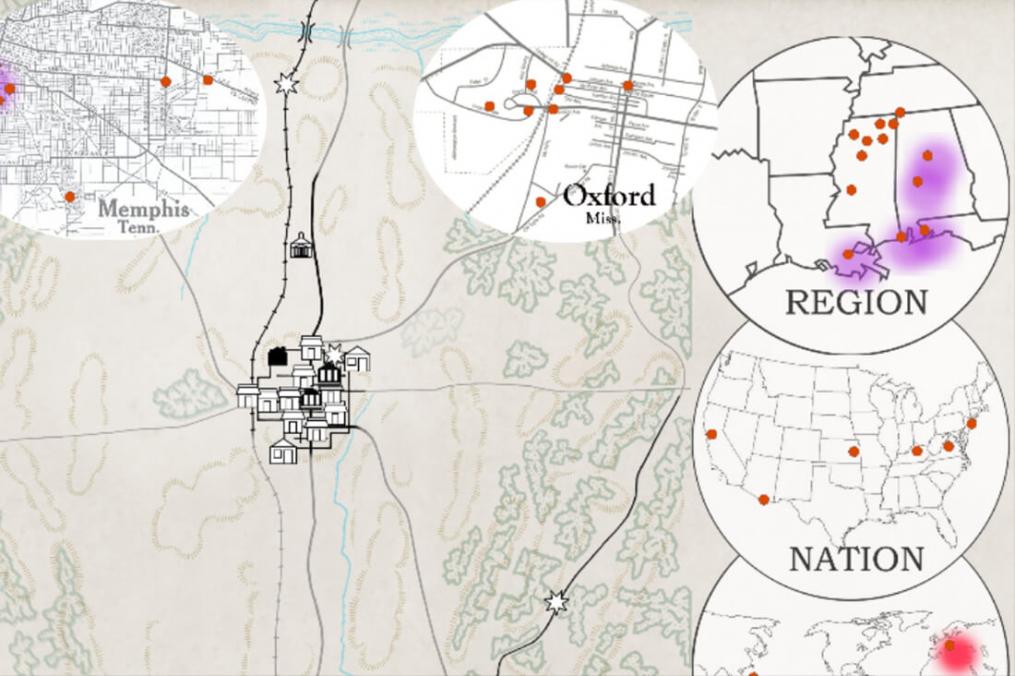

The project centers on the 15 novels and 48 short stories Faulkner wrote between 1926 and 1960 that were set in Yoknapatawpha County. Over the next few years, Faulkner scholars will collaborate to translate the characters, timelines, dialog, and events of these works into interactive online maps that will help readers visualize and glean new insights into Faulkner’s works.

The scholars aren’t working completely from scratch. According to Dr. Joiner, Faulkner himself drew a map of Yoknapatawpha, indicating locations and events portrayed in his stories.

“He considered it his little postage stamp of native soil of which he was sole owner and proprietor. Thus, this project is attempting to digitalize his fiction and expand on his mapping,” says Dr. Joiner.

Dr. Joiner says the attention to detail required in each scene “is a very different type of reading and interpretation than I’m used to doing,” as what seems relatively simple actually involves complex analysis. The text must be examined to determine whether a location is generated from explicit wording in the story, from one of Faulkner’s original maps, or through interpretive reasoning. Where one scene may state that “a conversation occurs in ‘the cabin,’” another event may take place a “two days ride away,” says Dr. Joiner.

“How does one map this?” she asks. “Which direction? How far is a day’s ride? Or if a character leaves at sunup and arrives at sundown, how far is that?”

Further mapping characters or even conversations between characters is similarly challenging, even in determining which are worth of mapping, says Dr. Joiner. Mining the narrative in this way for details “requires a lot of thought and interpretation in relation to other events in the narrative,” she says, adding, “it’s also causing me to look at narrative structure in ways I’ve never done before.”

Although the project is not finished, the current working prototype is live online. It offers scholars a way to enter characters, locations, and events from separate works into a robust database that then maps that data into an atlas of interactive visual resources, according to the demands of each particular story.

Ultimately, each work will have its own map, cross-referenced against others, enabling readers to pinpoint a specific location and review the breadth of characters in all Faulkner’s fiction that have a relation to that place as well as the timeline of events that happened there.

“The really exciting thing is that the entire project is a research project and the range of opportunities for what we can do with the data may not yet be discovered,” she says.